For decades, Alzheimer’s research was largely a story about amyloid — the sticky plaques that build up between brain cells and became the prime suspect in the disease’s destruction. Billions of dollars and countless clinical trials later, drugs that clear amyloid have shown frustratingly little benefit for patients. Now, the field is increasingly turning its attention to tau, the other notorious protein in the Alzheimer’s story. And a striking new discovery from the University of New Mexico suggests we may have just found a previously unknown master switch to turn it off entirely.

What Is Tau, and Why Does It Matter?

Under normal conditions, tau helps stabilize microtubules that give neurons their structure. Problems arise when tau undergoes phosphorylation — a chemical modification that causes it to form tangled clumps inside neurons. These neurofibrillary tangles are a defining feature of Alzheimer’s disease and more than 20 other neurodegenerative disorders, collectively known as tauopathies. As treatments targeting amyloid have repeatedly stumbled, tau has moved to center stage.

An Unlikely Discovery

The UNM team wasn’t originally hunting for a tau solution. Researchers were originally studying OTULIN — an enzyme known for regulating immune activity — for its role in cellular cleanup when they discovered its unexpected influence on tau production. What they found stopped them in their tracks: disabling OTULIN completely stopped tau production and removed existing tau from neurons. They achieved this by either using a specially designed small molecule or by knocking out the gene responsible for making OTULIN.

The experiments were conducted on two types of human cells — cells derived from a person who had died from late-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s disease, and human neuroblastoma cells commonly used in laboratory research. Crucially, the neurons didn’t appear to suffer. After the edit, the neurons kept their usual look in culture rather than showing signs of injury or stress. Markers of neuron survival stayed steady, suggesting neurons can apparently survive without tau.

Why This Is Different

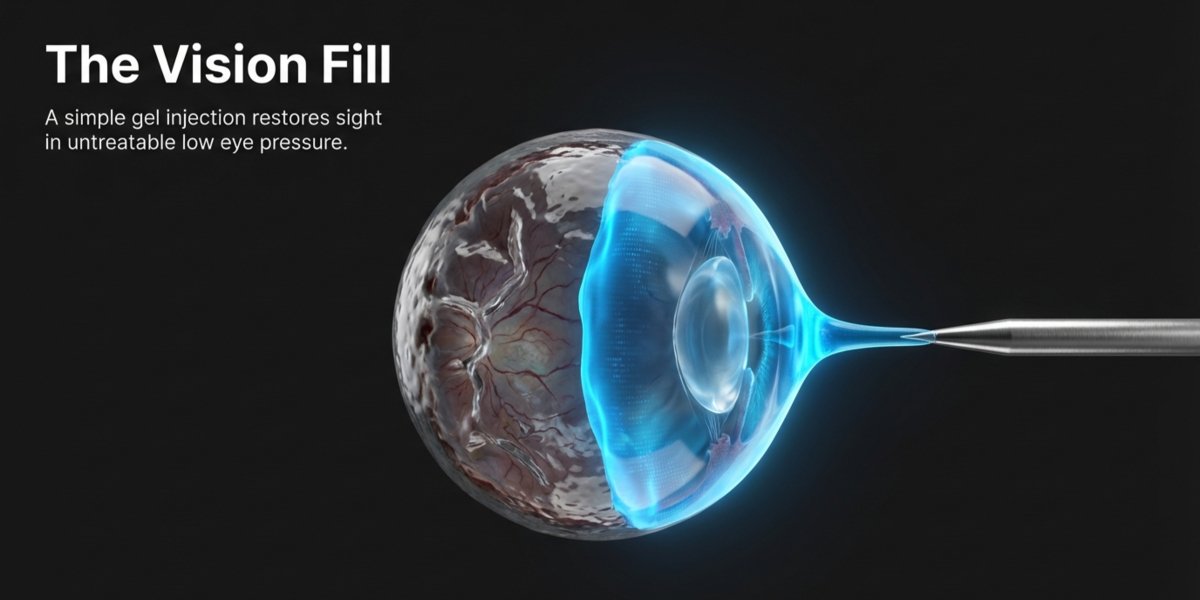

What makes this discovery particularly compelling is where it intervenes. Rather than simply clearing tau proteins after they’ve already formed — the approach most existing strategies attempt — tau’s disappearance began earlier, at the level of messenger RNA. Without that message, the tau-making gene could not supply fresh protein, meaning the cell had nothing to clear. It’s the difference between mopping up a flood and turning off the tap.

The team also identified a small molecule called UC495 that can slow OTULIN without deleting it entirely — a potentially important distinction for clinical use. Such a gap between slowing and deleting OTULIN hints that any future therapy may need fine control, not brute force.

Reasons for Cautious Optimism

There are important caveats. Removing tau from a dish is not the same as clearing it from a living brain, where many cell types interact. Future work must prove the same approach stays safe in animals and in other brain cells, not just neurons grown in dishes. Disabling OTULIN also has wide-ranging effects on gene expression, which introduces complexity around safety that will need careful navigation.

Still, the momentum building around tau is hard to ignore. Separate recent research from UCLA, UCSF, and the University of Cambridge has independently identified other promising mechanisms for clearing tau, suggesting the field is converging on the problem from multiple directions at once.

For the more than 55 million people worldwide living with dementia, that convergence can’t come soon enough.